There was a moment, which didn't last long in truth, when it seemed that glass resin (more technically defined as GRP, polyester reinforced with glass fibre) could compete for second place on the list.

Then there is another material, which for almost twenty years has been a bit of a Cinderella of Italian winemaking: good old concrete.

Having passed from composing, from the end of the 19th century and then especially in the 50s and 60s of the twentieth century, the good part of the cellars in our country - also structurally, in the sense that the barrels were often incorporated into the walls of the vat rooms - then underwent the backlash of modern materials: the fiberglass meteor, and finally steel, which displaced cement from the wine tank market.

Now we are witnessing his return, at first on tiptoe and gradually more and more undeniable, thanks to his performances: some well known to experts, others new and not yet verified.

Its comeback is well exemplified by the success that this sector is having within an Italian company that has made the history of concrete barrels: Nico Velo Spa of Fontaniva, in the province of Padua.

Nico Velo, after being the first in Europe to produce these tanks on an industrial scale, in 1950, had progressively set aside the wine sector, dedicating itself, starting from the mid-1960s, to the construction of industrial warehouses, a sector which still represents the major budget item of the company.

However, despite the apparent obsolescence of this material, the administration did not want to completely abandon the concrete barrels, maintaining a small production, which for up to three years corresponded to a paltry 5% of the entire company turnover.

The positive trend we are talking about has led to a significant leap in the last three years, which has raised the production of wine tanks to 20% of the 2013 annual budget, corresponding to a figure around 2.5 million euros.

Something has therefore changed, " because the wine production system has been revised, the logic has changed " according to Paolo Velo, grandson of the company's founder and responsible for the production of reinforced concrete tanks.

Until the 1970s, there were nine other shipyards in Fontaniva that produced and exported concrete barrels to Europe. Why right there? Thanks to the natural availability and in large quantities of the so-called "Brenta aggregates".

Inert materials or aggregates are a large category of “granular, particulate, raw mineral materials used in construction. They can be natural, artificial or recycled from materials previously used in construction. Aggregates include, but are not limited to: sand, gravel, expanded clay, vermiculite and perlite. They are used in construction, mainly as components, for example, of cement conglomerates" (source www.enco journal.com).

Brenta aggregates, thanks to their high crystallization capacity, favor the production of a very good cement mixture.

At the time, therefore, the high quality of the raw material allowed us to compete well on weight, a fundamental factor at the time of transport; Nico Velo could produce tanks whose walls did not exceed 4 centimeters in thickness.

As already mentioned, in the 1980s, steel ousted concrete. But not in France, where this material has never undergone a real decline, perhaps due to the different production logics that have characterized this country: " The French - says Paolo Velo again – they always let it pass at least two years before the wine is put on the market. This posed storage problems for them. Instead in Italy, for a long period, the logic of immediate consumption predominated, so steel was good in any case". Nico Velo has therefore continued to produce barrels with only the French market as its reference market: still 80% of the turnover of this company sector is due to orders from beyond the Alps.

A small myth to dispel is the cheapness of concrete compared to steel. Margins have reduced considerably in recent years, especially since the industrial production of cement allows for rather limited mechanization: a large part of the production steps are still manual; in fact, the completion of a small barrel requires on average a week of work by a team of specialized workers. Furthermore, transport costs still have a significant impact on the final price.

One of the great points against concrete barrels, which had largely determined their abandonment by producers, was that of the internal lining. At the time the internal resins caused hygienic, release and sealing problems over time.

This introduces one of the great themes regarding the technology of these containers, which once again sees us pitted against our French cousins.

It must be said first of all that the lion's share in the international marketing of cement barrels was played by Nomblot, a historic French company founded in 1922. It has the merit of having generated a new and strong interest in cement, and also of having created the now famous “egg shape” – abroad these barrels are known as “ concrete eggs ”. Nomblot has removed the concrete barrels from the storage corner, to fully introduce them into the category of tanks suitable for fermentation as happened in the past.

The big difference between the two companies in question lies precisely in the internal coating: in Italy, where the legislation requires coating using epoxy resin, Nico Velo sells painted barrels, while the majority of those destined for foreign countries are without coating, instead Nomblot mainly deals with barrels not coated in "natural cement".

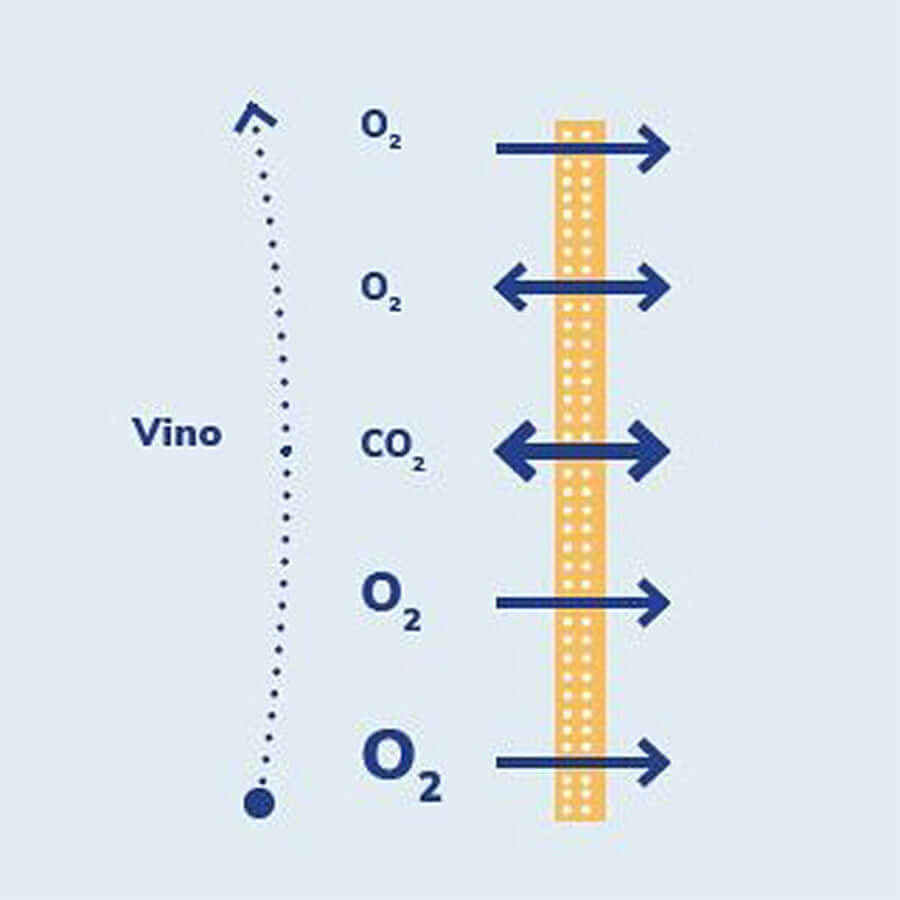

This last factor was decisive for the adoption of these barrels by producers of biodynamic wines, according to which the "egg shape" (the comparison with amphorae is not accidental) would favor the kinesis of the must, furthermore the cement uncoated would allow better micro-oxygenation and partial heat absorption, reducing the risk of reduction and leaving the acidity unchanged.

The conditional is a must, because there are no scientific studies to validate these statements. The absence of data provided by official research institutes is, in fact, one of the most evident characteristics of the topic: the rediscovery of this material is exclusively based on practical experiences and theoretical considerations but not on scientifically validated experimental data. According to Danilo Drocco, oenologist from Fontanafredda – one of Nico Velo's main Italian clients – the reason for this lack of interest lies in the age of the material. That is, it is not a new product, unknown to the market, but rather a historical material, forgotten for a while, but always present in our cellars and in recent decades also re-evaluated due to the favor given to it by famous winemakers, first of all Giacomo Tachis.

In an attempt to remedy this void, Nico Velo had tried to start a collaboration with the University of Pisa a few years ago, which unfortunately failed due to numerous technical and bureaucratic difficulties, which then pushed the company to turn to Giotto Consulting , a Treviso wine consultancy company that has a cutting-edge analysis laboratory. A trial has therefore been activated for a year and a half at the Azienda Agricola Corte Sant'Alda, in Mezzane di Sotto, in the province of Verona. Regarding the project, Federico Giotto, owner of the laboratory, says:

“ Our research initially focused on evaluating the differences between natural cement passivised with tartaric acid, vitrified cement, steel and wood. In this test, the possible transfers of all metals from the natural cement were evaluated by determination with ICP mass. In addition to this, we evaluated the evolution of the wines through the classic parameters, including that of dissolved oxygen, to verify possible microoxygenation phenomena. Our research has now focused on the study of different types of materials and the correct method of passivation of concrete tanks with tartaric acid. The research will be completed by the end of the year. The data found is the property of Velo Spa, the only company to date to carry out in-depth research in this sense ."

Therefore, while waiting for a definitive scientific theory, it is the law that is decisive: in Italy the local health authorities demand epoxy resin, in France however treatment using tartaric acid is also contemplated. The old way of doing the "treatment" is known: since it took place on site, the tanks were filled with low-quality wine, which was left there until the walls were soaked. In short, a bit of what Emidio Pepe calls "racia": “Wine doesn't do well in steel barrels, it doesn't fit well, to isolate itself from the steel it undresses. At the first transfer he takes off his jacket, then his shirt, then he remains naked. A rough layer forms in the concrete barrel, which remains and makes the wine a home. Wine is a son who doesn't speak or scream, you have to know how to listen. Glass is the natural habitat, the just house, the wine is a living being, on the light side it forms the dark layer, the race, this is what protects it.” Source: www.acqua-buona.it.

We asked Danilo Drocco again what he thought of the controversy over interior trim. It is worth remembering that Fontanafredda has had concrete tanks since 1858 which were already covered with glass tiles at the time.

“ If buying an untreated concrete tank means having it maintained every three years – claims Drocco, you might as well buy it permanently covered. I would never use a non-resined tank, since it is indisputable that a coated barrel is better sanitized ."

In fact, the Borgogno winery, a recent acquisition in the Farinetti orbit, was supplied exclusively with lined cement barrels: 12 100 hectoliter tanks, equipped with a cooling system with refrigerant liquid pipes. The possibility of better controlling the temperature has given a versatility previously unknown to concrete tanks, increasingly used for the fermentation, even of young wines.

In Fontanafredda the fermentation of Barolo has always taken place in concrete tanks because, unlike steel tanks, these old containers do not disperse heat and it is therefore possible to maintain a slightly higher average temperature during the fermentation phase. During the maceration phase, temperature stability favors the extraction and evolution of more complex tannic structures.

Cement therefore, as a poor conductor, is also perfect - again according to Drocco - for malolactic fermentation, because it keeps the temperature stable at around 21° for 15-20 days. Finally, but this has already been said, the Serralunga company has always used this material for refinement, following the passage in wood, precisely because the wine undergoes fewer vibrations, fewer heat changes, less oxygenation. On this last point, oxygenation, we need to insist further, since there are truly different visions of the cement effect. While Drocco claims that there is no increase in microoxygenation - or at least, that is not the effect sought by the Fontanafredda winemaker

– on the other side of the world, in South Africa, there are those who consider it a valid alternative to wood. This is what was claimed by Eben Sadie, of The Sadie Family, guru of the Swartland Revolution and one of the main supporters of untreated concrete: " I was looking for a material that was an alternative to wood, but which still allowed the wine to breathe, and which did not gave a woody flavor, since it is not part of the terroir. Concrete allows for a high level of purity in the expression of place .” (Source: www.winewisdom.com, author's translation)

The theme of oxygenation is directly connected to that of shape, which was also one of the main reasons for the success of the Nomblot "eggs".

Manufacturers who use the concrete eggs argue that the shape is responsible for more uniform convective motions. From the columns of Sally Easton MW's blog, we report the words of Gilles Lapalus, owner of Sutton Grange Winery and the first importer of Nomblot barrels in Australia: " Thanks to this shape there are no dead corners, resulting in better uniformity in the composition of the liquid , especially from the temperature point of view. The kinetic characteristics of fermentation seem more regular ”. (Source: www.winewisdom.com, translated by the author)

Regarding Italian barrels, Paolo Velo's opinion is frank: “ Le The first barrels, in the 1950s, were cylindrical in shape with a rounded bottom. Subsequently, when the use turned to storage, the quadrangular, parallelepiped shape clearly prevailed , above all for a question of saving space.

Having noticed the renewed attention towards the material, but above all the shift in the axis of interest - no longer, or not only, barrels for storage, but also for fermentation - the company has undertaken a phase of research and development of new barrels, with more rounded shapes.

This is how the barrels were born, from truncated pyramids to tulips truncated conical ones, which now make up the vat cellars of important Italian companies, we have already talked about Borgogno in Piedmont, but there are also Querciabella in Tuscany, Musella in Veneto and international ones: Château Prieuré Lichine, Cheval Blanc, Chapoutier - well yes: precisely the main proponent of the success of Nomblot, following the "divorce" from it, since 2009 it has turned exclusively to Nico Velo Spa - just to name a few.

Little changes, claims Paolo Velo, in the internal forms, which are almost the same as always. The battle is now played on aesthetics, since the cellars are open to the public and must be beautiful to look at.

In short, many interpretations and opinions, even controversial ones, have been expressed on concrete. This is a sign of the great interest it is creating around itself. The hope is that clarity will be clarified on the true pros and cons of this material: vitrification using epoxy resin or treatment with tartaric acid? Is the presumed greater microoxygenation measurable? Does the rounded shape favor the convective motions of the must?

All questions for which there is no answer yet. In the meantime, one cannot help but notice that even in the world of wine, communication works by inertia: when we talk about cement, the connection with Nomblot is immediate, the pioneering French company which has actually been at the forefront of the sector. . Nevertheless, chapeau also to our local Nico Velo Spa and its barrels, which since 1950 have brought prestige to the Italian wine industry in the world.

Adapted from:

Mille Vigne - The periodical of Italian winemakers, vol. 03 / 2014